Peer Reviewed

Mastoiditis Caused by Streptococcus intermedius

AUTHORS:

Trisha Modi, MD1 • Ganesh Maniam, MD1 • Peyton Bluhm, MD1 • Walker Payton, MD2 • Richard Lampe, MD2

AFFILIATIONS:

1Texas Tech University Health Sciences Center, Lubbock, Texas

2Department of Pediatrics, Texas Tech University Health Sciences Center, Lubbock, Texas

CITATION:

Modi T, Maniam G, Bluhm P, Payton W, Lampe R. Mastoiditis caused by Streptococcus intermedius. Consultant. 2022;62(3):e19-e21. doi:10.25270/con.2021.06.00003

Received October 9, 2020. Accepted January 11, 2021. Published online June 3, 2021.

DISCLOSURES:

The authors report no relevant financial relationships.

CORRESPONDENCE:

Trisha Modi, BS, MBA, Texas Tech University Health Sciences Center, 3601 Fourth Street, Stop 6238, Lubbock, TX 79430 (Trisha.Modi@ttuhsc.edu)

A previously healthy 8-year-old boy presented to our emergency department (ED) with sudden-onset neurological deficits and altered mental status following a syncopal episode. Upon admission, the patient reported symptoms of photophobia, ataxic gait, and abdominal pain.

History. The patient’s mother reported fevers and vomiting on and off for 7 days prior to admission, which did not improve with acetaminophen, ibuprofen, or elderberry. She also reported a preference for naturopathic medicine and significant essential oil use. The patient had no significant medical history and denied having a primary care provider or any vaccinations after age 4 years.

Physical examination. In the ED, the patient had hypotension (blood pressure, 99/65 mmHg), tachycardia (heartbeat, 152 beats/min), tachypnea (32 breaths/min), and a fever of 38.06 °C. He was emaciated, ill-appearing, pale, and intermittently responsive. On physical examination, the patient had a bulging right tympanic membrane with frank pus. Therefore, the patient was admitted.

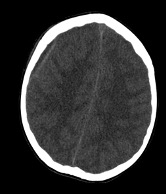

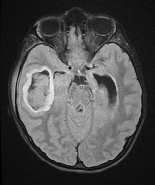

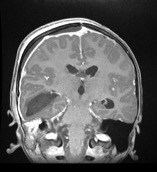

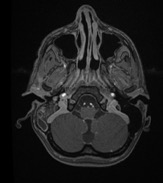

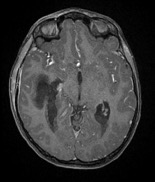

Diagnostic testing. Findings from the laboratory studies revealed an elevated white blood cell count of 33.09 c/mL, an elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate of 122 mm/hr, and an elevated procalcitonin level of 9.61 ng/mL. Thus, the patient was started on cefepime and levetiracetam. Imaging studies demonstrated mastoiditis, a large right temporal collection of fluid concerning for early cerebritis, and ventriculitis with abscess formation and local mass effect (Figures 1-4).

Figure 1. Axial images of computed tomography scans of the head demonstrating (a, top) opacification of right mastoid sinus and right middle ear consistent with a diagnosis of otomastoiditis, (b, middle) subdural empyema in the right convexity, and (c, bottom) an ill-defined area of low attenuation in the right temporal lobe suspicious for underlying infection or mass.

Figure 2. Axial T2 flair magnetic resonance imaging demonstrated a right temporal lobe abscess.

Figure 3. Postcontrast coronal magnetic resonance imaging demonstrated a large right temporal collection concerning for early cerebritis with abscess, decompressing into the ventricular system with presence of ventricular abscesses. There is evidence of pachymeningitis and small right frontoparietal epidural abscess with local mass effect.

Figure 4. Postcontrast axial magnetic resonance imaging demonstrated (a, top) mastoiditis and (b, bottom) a right temporal lobe abscess decompressing into the ventricular system, with presence of ventricular abscesses.

After consulting with a neurosurgeon and an otorhinolaryngologist, ceftriaxone per sensitivities and metronidazole for anaerobic coverage were initiated. On hospital day 2, the patient continued to have a guarded prognosis with minimal neurologic improvement. A left-sided external ventricular drain was placed, and a craniotomy was performed to evacuate the brain abscess, right cortical mastoidectomy, and right tympanostomy tube placement.

On hospital day 9, the patient was septic with blood cultures positive for Streptococcus intermedius. The patient was switched from cefepime to ceftriaxone, while imaging results indicated a severe and chronic infectious process despite maternal denials of progressive symptoms. Because of a significant leak from the neurosurgical incision at this time, the patient underwent a right temporal craniotomy and duraplasty with fascial graft, debridement and drainage of the right temporal wound, placement of a right frontal external ventricular drain, and removal of the left external ventricular drain.

On hospital day 18, the left external ventricular drain was removed, and a left external ventricular shunt was placed due to postinfectious hydrocephalus. Intravenous metronidazole was discontinued on hospital day 29 because of multiple weeks of significant anaerobic coverage.

Discussion. Streptococcus anginosus is the most commonly implicated bacterial pathogen in complicated cases of pediatric rhinosinusitis.1 At the same time, this group of infections is also associated with higher rates of neurosurgical treatment, as well as long-term neurological complications.1 The onset of S intermedius brain abscess formation is typically chronic, beginning with tissue damage that precedes bacterial colonization, liquefaction, and pus formation through hyaluronidase activity.2 Our case presents a previously healthy pediatric patient who presented with sudden syncope and altered mental status, which was ultimately revealed to be due to a massive intracranial abscess caused by S intermedius.

The pathogenesis of pediatric mastoiditis, as well as its intracranial manifestations, are often a complication of acute otitis media—the pus extends anteriorly into the canal wall and posteriorly into the sigmoid sinus of the posterior cranial fossa.3 Such suppurative intracranial complications are rare, with the incidence of the progression from acute otitis media to severe mastoiditis estimated to be less than 0.004%, but these complications are certainly associated with significant morbidity and long-term neurological deficits. The patient in this case had reported no clinical signs of otitis media prior to admission.3

S intermedius infections, as seen in our patient, are more common among boys and commonly present with intermittent fever and consistent headaches, with dental manipulation and sinusitis as underlying risk factors.2 A third-generation cephalosporin and metronidazole are the standard treatments for S intermedius infections, with metronidazole being the most commonly prescribed.2

Our case may assist physicians to earlier recognize and treat atypical cases of mastoiditis with S intermedius in which there is a lack of preceding symptoms of sinusitis, presence of minimal inflammation in the mastoid region, or presentation as sudden-onset syncope. Clinical suspicion is warranted upon the presentation of a pediatric patient with “picket fence” fever, vomiting, and drowsiness; mastoid swelling may or may not be present in such cases.4 With no significant trauma or sinusitis, the etiology of the initial mastoiditis in this patient remains unknown. Our patient likely had an indolent course with progression for months prior to the sudden-onset neurologic deficits leading to hospitalization.

Patient outcome. On hospital day 31, the patient was discharged to inpatient rehabilitation. He was discharged on levetiracetam seizure prophylaxis and intravenous ceftriaxone therapy for 6 to 8 weeks. Repeat laboratory studies were also recommended every 2 weeks to monitor his white blood cell count. He has a follow-up with neurosurgery for a rapid magnetic resonance imaging scan scheduled for 6 weeks after discharge.

References

1. Deutschmann MW, Livingstone D, Cho JJ, Vanderkooi OG, Brookes JT. The significance of Streptococcus anginosus group in intracranial complications of pediatric rhinosinusitis. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2013;139(2):157-160. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamaoto.2013.1369

2. Issa E, Salloum T, Tokajian S. From normal flora to brain abscesses: a review of Streptococcus intermedius. Front Microbiol. 2020;11:826. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2020.00826

3. Subramaniam S, Ang A, Tan HKK. Mastoiditis presenting as parietooccipital scalp abscess—a case report and literature review. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol Extra. 2012;7(2):82-84. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pedex.2012.01.003

4. Krishnan M, Walijee H, Jesurasa A, et al. Clinical outcomes of intracranial complications secondary to acute mastoiditis: the Alder Hey experience. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2020;128:109675. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijporl.2019.10967