A Middle-Aged Male with Progressing Blurry Vision

History

A 49-year-old male with a history of hypertension presented with a 2-week history of blurry vision, which was first noticeable in the peripheral vision of his left eye. This progressed to involve the peripheral vision in his right eye as well. He then began to notice that his central vision was becoming blurry in both eyes, and at times, he seemed to have horizontal double vision.

There was no associated headache or pain. He denied trauma to his head or eyes. He did not wear contact lenses. He also denied flashers or floaters in his vision, photophobia, difficulty speaking or swallowing, numbness or tingling in his face, or dizziness.

There is a family history of a cerebral aneurysm in the patient’s mother.

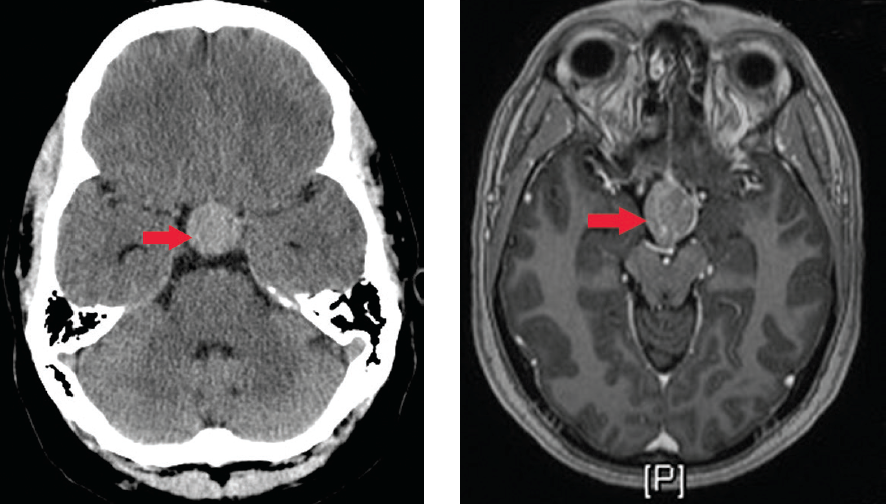

Figure 1. Head CT showing a pituitary macroadenoma.

Figure 2. Axial T1 post-contrast MRI.

Physical Examination

On examination, the patient was well appearing, sitting on the exam table, with lights on and in no distress. His vitals were: pulse of 80 beats per minute, blood pressure of 122/84 mm Hg, respiratory rate of 12 breaths per minute, oxygen saturation at 95%, and temperature of 36.8°C.

Laboratory Tests

Exam of his eyes revealed no injection both eyes at gross inspection; visual acuity of 20/25 in the right eye and 20/30 in the left eye; intraocular pressure was 17 in the right eye and 19 in the left eye. Pupils were round and reactive to light, 4 mm to 2 mm with no afferent pupillary defect in both eyes. Extraocular movements were full and intact in both eyes and the visual fields revealed temporal hemianopsia in both eyes. Slit lamp revealed no cell and flare in both eyes. An ophthalmoscopic exam showed no papilledema in both eyes.

The neurological examination was normal with the exception of his visual fields as noted above.

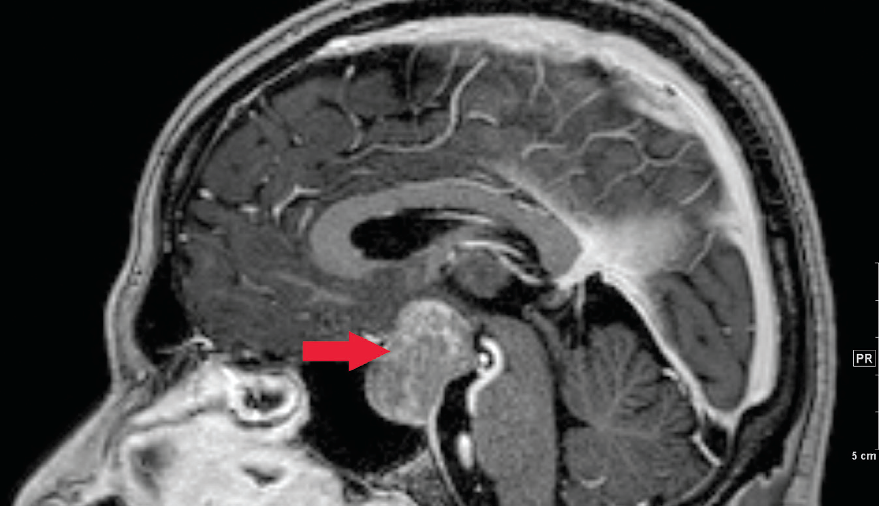

Figure 3. Sagital T1 post-contrast MRI.

What’s Your Diagnosis?

A. Migraine

B. Retinal detachment

C. Pituitary adenoma

D. Cerebral vascular accident

(Answer and discussion on next page)

Answer: Pituitary adenoma

Ophthalmology was consulted in the emergency department and was unable to find any ocular etiology. A CT of the head was recommended to rule out any obvious brain etiology. A noncontrasted CT head revealed a hyperdense mass, measuring approximately 2 cm. The mass enlarged the sella turcica and extended into the suprasellar cistern and obscured the optic chiasm and tracts, which likely represented a pituitary macroadenoma (Figure 1).

Discussion

Pituitary adenomas are the most common cause of sellar masses and typically present in a variety of ways—with neurologic symptoms (eg, visual impairment or headache), hormonal abnormalities, or as an incidental finding on head imaging. They are benign tumors of the anterior pituitary and are classified by size and the cell of origin.

Lesions <1 cm are classified as microadenomas and lesions >1 cm are classified as macroadenomas. The tumors can arise from any type of cell of the anterior pituitary and may result in increased and/or decreased secretion of other hormones due to compression of other cell types.

The degree of hormone production does not always correlate with tumor size. Gonadotroph (luteinizing hormone, follicle-stimulating hormone) adenomas usually present as clinically nonfunctioning sellar masses. Thyrotroph (TSH) adenomas may present as clinically nonfunctioning sellar masses that secrete only alpha- or TSH-beta subunits or may cause hyperthyroidism due to increased secretion of intact thyroid stimulating hormone. Corticotroph (adrenocorticotropic hormone) adenomas usually cause Cushing’s disease. Lactotroph adenomas usually cause hyperprolactinemia, which leads to hypogonadism in women and men. Somatotroph adenomas typically cause acromegaly due to increased growth hormone secretion.

Other causes of sellar masses include pituitary hyperplasia, benign tumors (eg, craniopharyngioma, meningioma, pituicytoma), primary malignant tumors (eg, germ cell tumors, chordomas, primary lymphoma), metastatic disease, cysts, abscess, arteriovenous fistula of the cavernous sinus, and hypophysitis.

Clinical Manifestations

Impaired vision is the most common symptom that leads a patient with a nonfunctioning adenoma to seek medical care. Visual impairment is caused by suprasellar extension of the adenoma, leading to compression of the optic chiasm.

The most common complaint is diminished vision in the temporal fields—ie, bitemporal hemianopsia. One or both eyes may be affected; if both, to variable degrees. Loss of red perception is an early sign of optic tract pressure. Diminished visual acuity occurs when the optic chiasm is more severely compressed. Other patterns of visual loss can also occur.

Other neurologic symptoms may include headaches; diplopia induced by oculomotor nerve compression resulting from lateral extension of the adenoma; pituitary apoplexy induced by sudden hemorrhage into the adenoma that causes excruciating headache and diplopia; cerebrospinal fluid rhinorrhea caused by inferior extension of the adenoma; and Parinaud syndrome—a constellation of neuro-ophthalmologic findings, most often paralysis of upward conjugate gaze, that result from ectopic pinealomas.

Hormone deficiencies may be elicited after careful questioning of patients who initially present due to a neurologic symptom. The most common pituitary hormone deficiencies are of gonadotropins, resulting in hypogonadism in both men and women. In men, symptoms of hypogonadism include breast enlargement, decreased body hair, muscle loss, decreased libido, and erectile dysfunction. In women, symptoms include hot flashes, decreased body hair, low libido, and cessation of menstruation.

Evaluation and Management

Sellar masses should be evaluated radiographically, hormonally, and with ophthalmologic evaluation.

• MRI. This is the single best imaging procedure for most sellar masses. On unenhanced MRI imaging, normal pituitary tissue and most pituitary adenomas have a signal that is similar to or slightly greater in intensity than that of CNS tissue.

On gadolinium-enhanced MRI imaging, normal pituitary tissue takes up gadolinium to a greater degree than CNS tissue and therefore, has a higher intensity signal than the surrounding CNS. The degree of gadolinium enhancement, however, does not distinguish one kind of sellar mass from another.

CT imaging has a limited role in characterization of these masses although it may be the initial imaging study that identifies the mass.

• Hormone evaluation. This includes measuring basal prolactin, insulin-like growth factor-1, 24-hour urinary free cortisol and/or overnight oral dexamethasone suppression test, alpha subunit, FSH, LH, and thyroid function levels. Additional hormonal evaluation may be indicated based on the results of these tests.

• Ophthalmologic evaluation. Due to compressive effects on the optic chiasm, a complete ophthalmologic evaluation should be performed on all patients with sellar masses. This should include perimetry visual field testing to maps and quantify the visual field, especially at the extreme periphery of the visual field. Types of perimetry include the Goldman perimeter, kinetic and static, and standard automated perimetry, which is now used widely.

The goals of pituitary adenoma treatment include normalization of excess pituitary secretion (if present) as well as shrinkage and/or resection of large adenomas to relieve adjacent structure compression, thus limiting the potential for long-term visual disturbances. Transsphenoidal resection, rather than transfrontal resection, is the preferred surgical approach whenever possible.

The extent of the evaluation in a patient with an incidentally discovered intrasellar MRI signal abnormality (eg, pituitary incidentaloma) depends upon its size. If it is >1 cm, hormonal evaluation is recommended, and resection should be considered. If it is <1 cm and the patient has no clinical findings of pituitary dysfunction, the extent of evaluation is controversial and ranges from measuring only the serum prolactin concentration to measurement of multiple hormones and scheduling a follow-up MRI at 12 months and beyond.

Migraines

Migraines are the second most common cause of headache and afflict women more than men. The 2004 International Headache Society Classification outlines the diagnostic criteria for migraine headaches to include:

• Repeated attacks of headache lasting 4 to 72 hours in patients with a normal physical examination

• No other reasonable cause for the headache

• At least 2 of the following features: unilateral pain, throbbing pain, aggravation by movement, moderate or severe intensity

• At least 1 of the following features: nausea/vomiting or photophobia/phonophobia

Visual disturbances in the migraine aura consist of flashing lights or zigzag lines moving across the visual field, and are reported in only 20% to 25% of patients. These disturbances remain visible in the dark and with the eyes closed. They are generally confined to either the right or left visual hemifield, but sometimes both fields are involved simultaneously. Severe migraine attacks may require parenteral therapy with 1 of 3 major pharmacologic classes: anti-inflammatory agents (eg, ketorolac), 5-HT(1B/1D) receptor agonists (eg, sumatriptan, dihydroergotomine), and dopamine receptor antagonists (eg, metoclopramide).

Retinal detachment produces symptoms of floaters, flashing lights, and a scotoma in the peripheral visual field corresponding to the detachment. If the detachment includes the fovea, there is an afferent pupil defect and the visual acuity is reduced. Most commonly, retinal detachment starts with a fold, flap, or tear in the peripheral retina. Patients with a history of myopia, trauma, or prior cataract extraction are at greatest risk. The diagnosis is confirmed by ophthalmoscopic examination of the dilated eye and requires prompt consultation with ophthalmology once recognized.

Transient Ischemic Attacks and Cerebral vascular accident (CVA)

Vertebrobasilar insufficiency may result in acute homonymous visual symptoms. Many patients mistakenly describe symptoms in their left or right eye, when in fact they are occurring in the left or right hemifield of both eyes. Interruption of blood supply to the visual cortex causes a sudden fogging or graying of vision, occasionally with flashing lights that mimic migraine.

Cortical ischemic attacks are briefer in duration than migraines, occur in older patients, and are not followed by headaches. There may also be associated with signs of brainstem ischemia—such as diplopia, vertigo, numbness, weakness, or dysarthria.

A CVA occurs when interruption of blood supply from the posterior cerebral artery to the visual cortex is prolonged and is usually due to thrombotic occlusion of the vertebrobasilar system, embolus, or dissection. The only finding on exam is a homonymous visual field defect that stops abruptly at the vertical meridian. The diagnosis is made most commonly with a CT angiography and possibly a MRI. Management and the use of tissue plasminogen activator is dependent on the timing of the onset of symptoms and should be made in conjunction with a neurologist.

Outcome of the Case

The patient was admitted to the hospital for further evaluation and treatment. Neurosurgery evaluated the patient and recommended evaluation by endocrinology to determine pituitary function, MRI with and without contrast of the sella (Figures 2 and 3), and formal visual field testing by ophthalmology prior to surgical intervention. Endocrinology lab testing was negative for a pituitary secretory tumor. Outpatient transsphenoidal surgical resection by neurosurgery was scheduled. Unfortunately, the patient was lost to follow-up.

Emily Dodge, MD, is an attending physician in the department of emergency medicine at MetroHealth Medical Center and an assistant professor of emergency medicine at Case Western Reserve University School of Medicine, all in Cleveland, OH.

David Effron, MD, is an assistant professor of emergency medicine at Case Western Reserve University School of Medicine, attending physician in the department of emergency medicine at MetroHealth Medical Center, and consultant emergency physician at the Cleveland Clinic Foundation, all in Cleveland, OH.

Recommended readings

1. Dekkers OM, Hammer S, de Keizer RJ, et al. The natural course of non-functioning pituitary macroadenomas. Eur J Endocrinol. 2007;156(2):217-224.

2. Monteiro ML, Zambon BK, Cunha LP. Predictive factors for the development of visual loss in patients with pituitary macroadenomas and for visual recovery after optic pathway decompression. Can J Ophthalmol. 2010;45(4):404-408.

3. Orija IB, Weil RJ, Hamrahian AH. Pituitary incidentaloma. Best Pract Res Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2012;26(1):47-68.