Peer Reviewed

Hypertrophic Pulmonary Osteoarthropathy in an Older Woman

AUTHORS:

Rebecca DeBoer, DO1 • Anish Paudel, MD1 • Bryan Romero, DO1

AFFILIATION:

1Department of Medicine, Reading Hospital, Reading, Pennsylvania

CITATION:

DeBoer R, Paudel A, Romero B. Hypertrophic pulmonary osteoarthropathy in an older woman. Consultant. 2021;61(9):e42-e44. doi:10.25270/con.2021.02.00004

Received August 8, 2020. Accepted January 14, 2021. Published online February 10, 2021.

DISCLOSURES:

The authors report no relevant financial relationships.

ADDITIONAL CONTRIBUTIONS:

The authors would like to thank Michael Karchevsky, MD, from the Department of Radiology at Reading Hospital, Tower Health System, for providing the computed tomography scan of periostitis for the manuscript.

The authors would like to thank Anthony Donato, MD, from the Department of Internal Medicine at Reading Hospital, Tower Health System, for providing valuable insight.

CORRESPONDENCE:

Rebecca DeBoer, DO, 2101 State Hill Road, Suite 5, Reading Hospital, Reading, Pennsylvania, 19610 (rebecca.deboer@towerhealth.org)

A 62-year-old woman presented to our hospital with lower extremity pain. The pain had initially begun in her left leg distal to her knee. She had thought the pain was secondary to osteoarthritis. Then, approximately 1 month later, she developed severe pain in both knees and ankles, with pain worse on the left side. The pain was worse with sitting and improved with standing and moving. She also began to notice edema around her ankles. She did not report cardiac, respiratory, or gastrointestinal symptoms, and she had no history of fevers, night sweats, or weight loss.

History. The patient had a history significant for smoking 1.5 packs of tobacco cigarettes daily for 36 years. Her medical history included emphysema and hip osteoarthritis.

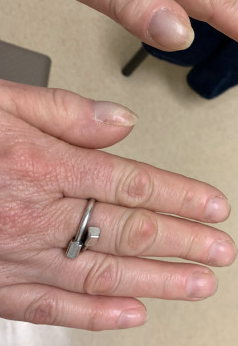

Physical examination. The physical examination revealed significant clubbing in the fingernails (Figure 1). There was bilateral and symmetric swelling in the lower extremities, obscuring the ankle joints. Both of her ankles were tender, with the left greater than the right, and both had preserved range of motion. Both of her knees were tender, with preserved range of motion. There was no erythema noted around the affected joints. Her shins were not tender upon palpation.

Figure 1. Digital clubbing of digits with convex nails and a general drumstick appearance.

Digital clubbing raised concern for underlying pulmonary disease. Therefore, chest radiography was conducted. The results showed 2 suspicious masses: a 7-cm mass in the left lower lobe and 3-cm mass in the right upper lobe (Figure 2). However, at this time, the suspicious lung masses and lower extremity pain were not connected. Results of an ultrasonography scan of lower extremities were negative for deep vein thrombosis. The pain was still thought to be secondary to osteoarthritis and the edema due to dependent edema.

Figure 2. The left retrocardiac opacity was also identified as left lower lobe mass. Expanded lesion in the right fourth anterior rib was identified initially as a right lower lobe mass.

The patient was started on hydrochlorothiazide, 12.5 mg, daily for the edema, which did not lead to significant symptom improvement. Her pain had continued to intensify. At that time, a bilateral lower extremity computed tomography (CT) scan was conducted (Figure 3), which showed diffuse periostitis involving the femur, tibia, and fibula.

Figure 3. CT scan of right lower extremity demonstrating an incomplete rim of periosteal reaction, consistent with periostitis.

With the digital clubbing, arthralgia, and periostitis, the diagnosis of hypertrophic pulmonary osteoarthropathy (HPOA) was made. The patient was started on celecoxib, 200 mg, twice daily to reduce the pain related to periostitis. Although celecoxib only partially improved her symptoms, the patient continued on this medication indefinitely.

To follow up on the suspicious chest radiography scan and diagnosis of HPOA, a chest CT was conducted. This revealed a 7.4-cm left lower lobe mass (Figure 4) highly concerning for malignancy given her history of emphysema and tobacco use. This lesion had broad contact along the pleura and along the left posterior mediastinum. An enlarged 16-mm left hilar lymph node was also noted. This corroborates the left lower lobe mass seen on the chest radiography scan. The presumed right upper lobe mass on chest radiograph scan was determined to be an expanded, sclerotic rib lesion, rather than a lung mass. A biopsy of the left lower lobe mass was performed, results of which were positive for adenocarcinoma.

Figure 4. CT scan of the chest showing left lower lobe mass concerning for malignancy.

A bone scan was also performed, results of which revealed suspected T5 vertebral and manubrial metastasis. Test results were negative for epidermal growth factor receptor and anaplastic lymphoma kinase markers. She was started on a chemotherapy regimen including carboplatin, pemetrexed, and pembrolizumab.

Discussion. Hypertrophic osteoarthropathy (HOA) is a syndrome comprising a triad of digital clubbing, arthritis or arthralgia, and periostitis.1 There are 2 forms of HOA. Primary HOA is rare and hereditary.1 Secondary HOA comprises 95% to 97% of all cases.1 Underlying lung malignancy accounts for approximately 90% of secondary HOA.1 Less common causes of secondary HOA include congenital cyanotic heart disease.1

HPOA is diagnosed when HOA is associated with underlying lung disease.2 The complete triad of clinical features is very rare among patients with HOA.3 In one retrospective study, while 4.5% of the patients with lung cancer had 1 of 3 of the features, only 0.8% had the complete triad.3 In comparison, nearly 50% of the patients diagnosed with HOA also had an underlying adenocarcinoma of the lung.3

The exact mechanism for HOA is unknown. However, 2 mechanisms are postulated for the pathophysiology. The first is a neurogenic pathway involving the vagus nerve.4 The second is a humoral pathway in which platelet-derived growth factor, prostaglandin E, and vascular endothelial growth factor all have a role in response to a state of hypoxia.1 The specific role of vascular endothelial growth factor has also been highlighted.5

Despite debate over the underlying pathophysiology of HOA, physical examination findings paired with imaging can give a definitive diagnosis. The hallmark signs of HOA, periostosis, or abnormal periosteal new bone formation can be visualized via imaging scans. Usually plain film is utilized, but CT scanning is also sufficient. Results of imaging will show symmetric involvement of tubular bones such as tibia, fibula, radius, and ulna.1 The CT scans of our patient’s lower extremities showed diffuse periostitis involving the femur, tibia, and fibula. A subsequent biopsy was positive for adenocarcinoma of the lung.

Treatment and management. The most important component of treatment is to treat the underlying condition. This may reduce the severity of the disease and lessen pain. Another effective pain management option is nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs.2,6 Celecoxib and the chemotherapy regimen had reduced our patient’s symptoms.

The critical step in this patient’s workup was the physical examination. Physical findings can lead not just to a diagnosis of HPOA but also to pulmonary malignancy. In this case, joint pain and digital clubbing were noted during the physical examination. Radiographic imaging elucidated the periostitis. All 3 may not always be present, though. Regardless, it will take a careful clinician to appreciate tenderness along the distal extremities and also to continue the search for abnormalities such as digital clubbing. This case reminds us to see the entire patient during the examination.

Patient outcome. The patient has already completed 4 cycles of the chemotherapy regimen. After the third cycle, there was a slight decrease in the size of the left lower lobe mass. She also completed stereotactic radiation to the bone metastasis and radiation to the chest.

References

- Yap FY, Skalski MR, Patel DB, et al. Hypertrophic osteoarthropathy: clinical and imaging features. Radiographics. 2017;37(1):157-195. https://doi.org/10.1148/rg.2017160052

- Pineda C, Martínez-Lavín M. Hypertrophic osteoarthropathy: what a rheumatologist should know about this uncommon condition. Rheum Dis Clin North Am. 2013;39(2):383-400. doi:10.1016/j.rdc.2013.02.008

- Izumi M, Takayama K, Yabuuchi H, Abe K, Nakanishi Y. Incidence of hypertrophic pulmonary osteoarthropathy associated with primary lung cancer. Respirology. 2010;15(5):809-812. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1440-1843.2010.01769.x

- Treasure T. Hypertrophic pulmonary osteoarthropathy and the vagus nerve: an historical note. J R Soc Med. 2006;99(8):388-390. https://doi.org/10.1258/jrsm.99.8.388

- Olán F, Portela M, Navarro C, et al. Circulating vascular endothelial growth factor concentrations in a case of pulmonary hypertrophic osteoarthropathy. Correlation with disease activity. J Rheumatol. 2004;31(3):614-616. https://www.jrheum.org/content/31/3/614

- Kaur H, Muhleman M, Balon HR. Hypertrophic osteoarthropathy on bone scintigraphy. J Nucl Med Technol. 2018;46(2):147-148. https://doi.org/10.2967/jnmt.117.199315