Peer Reviewed

Bilateral Serous Epithelial Detachment After Starting Therapy With Erdafitinib

AUTHORS:

Samantha Sauerzopf, MD • Jing Zhao, MD

AFFILIATIONS:

Geisinger Medical Center, Danville, Pennsylvania

CITATION:

Sauerzopf S, Zhao J. Bilateral serous epithelial detachment after starting therapy with erdafitinib. Consultant. 2021;61(7):e26-e29. doi:10.25270/con.2020.12.00003

Received July 2, 2020. Accepted November 6, 2020. Published online December 9, 2020.

DISCLOSURES:

The authors report no relevant financial relationships.

CORRESPONDENCE:

Samantha Sauerzopf, MD, Geisinger Woodbine Lane, 16 Woodbine Ln, Danville, PA 17821 (sasauerzopf@geisinger.edu)

A 67-year-old man with metastatic urothelial cancer was sent to the ophthalmology clinic for baseline testing before start of erdafitinib. His visual acuity (VA) was 20/30 in the right eye and 20/25 in the left eye. He denied any vision problems.

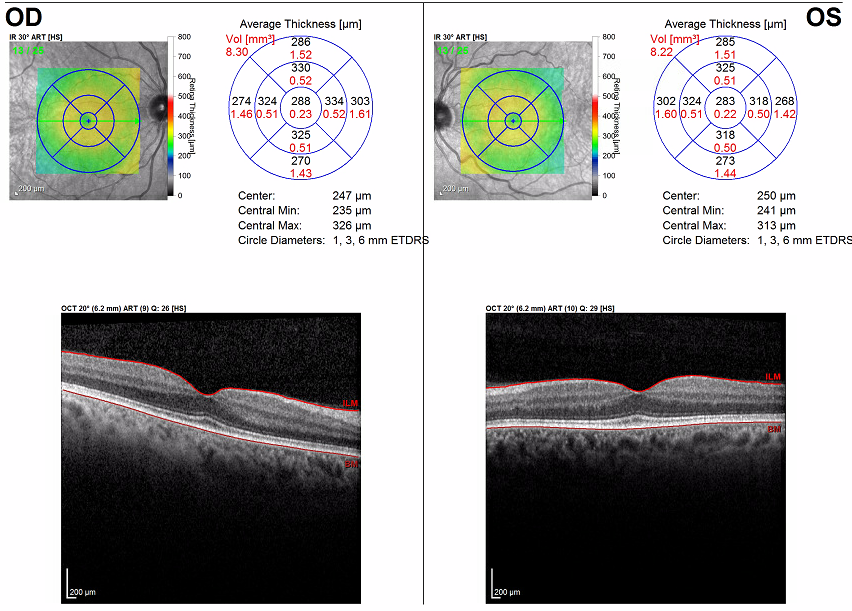

Anterior slit lamp examination findings were unremarkable. Dilated fundus examination findings were notable for posterior vitreous detachment bilaterally but were otherwise normal, with no lesions concerning for metastases nor any subretinal fluid or pigment epithelial detachment. The patient then underwent optical coherence tomography (OCT) for a more detailed view of the retina. OCT is a noninvasive imaging system used in ophthalmology to view the layers of the retina and/or optic nerve down to the micrometer in detail. The machine utilizes a broad light source Into the eye and then measures the reflectivity of the beam to detect an interference pattern in order to create high-resolution and cross-sectional imaging.1 Results of the OCT scans of the maculae were within normal limits bilaterally (Figures 1A and 1B).

Figure 1A. Baseline OCT scans of the maculae, right eye (right image) and left eye (left image). Both eyes were within normal limits, meaning that there is a well-visualized foveal dip in the center of the macula with the layers from top to bottom (retinal nerve fiber layer directly underneath internal limiting membrane [ILM], ganglion cell layer, inner plexiform layer, inner nuclear layer, outer plexiform layer, outer nuclear layer, external limiting membrane, ellipsoid zone, retinal pigment epithelium directly above basement membrane [BM] and choroid below the BM) without thinning, atrophy, or thickening. There is no subretinal fluid and a normal foveal contour.

Figure 1B. OCT scan of the macula with normal foveal dip centrally. Normal retinal layers, from top to bottom, are the retinal nerve fiber layer (RNFL) directly underneath internal limiting membrane (ILM), ganglion cell layer (GCL), inner plexiform layer (IPL), inner nuclear layer (INL), outer plexiform layer (OPL), outer nuclear layer (ONL), external limiting membrane (ELM), ellipsoid zone/IS/OS, retinal pigment epithelium (RPE) directly above basement membrane (BM), and choroid below the BM. The function of each of these layers of the retina is beyond the scope of this report.

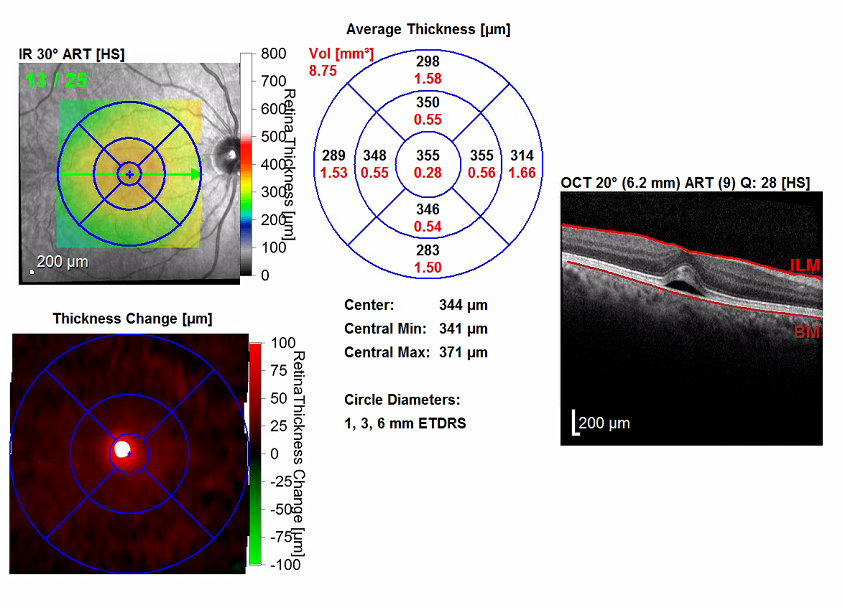

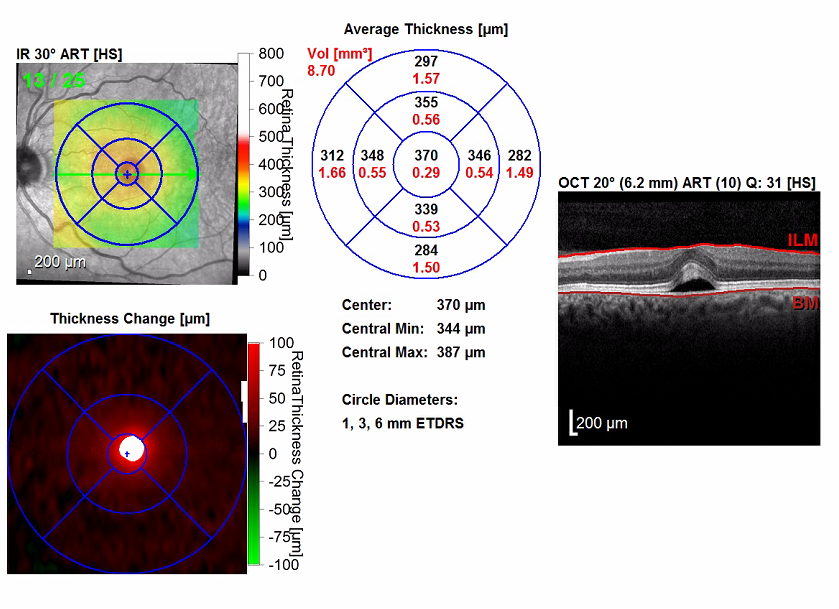

With clear ophthalmologic examination findings, in coordination with hematology-oncology specialists, the patient was started on low-dose erdafitinib, 4 mg, with up-titration over the next few weeks to 8 mg. He reported for his 1-month ophthalmology follow-up visit with no new subjective symptoms. However, his VA had been notably reduced to 20/40 in the right eye. On dilated examination, he was found to have blunting of the foveal reflex, suggesting the presence of subretinal fluid (Figure 2). Results of OCT of the macula showed bilateral serous detachments (Figure 3).

Figure 2. Color fundus photography posterior pole 30°, right eye (right image) and left eye (left image). Both eyes showed an optic disc with sharp margins, a cup-disc ratio within normal limits, and vasculature without tortuosity. The macula of both eyes showed blunted foveal reflex and focal elevation at the level of the fovea.

Figure 3. OCT scans of the maculae showed bilateral serous detachments and disruption of the foveal contour. The right eye (bottom images) had a significant increase in central retinal thickening, from 288 µm to 355 µm. The left eye (top images) had a significant increase in central retinal thickening from 238 µm to 370 µm.

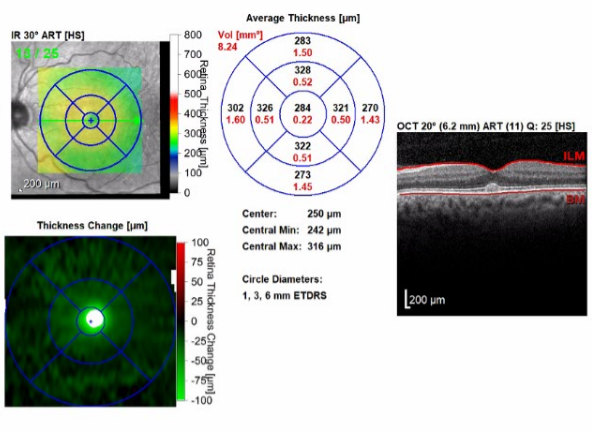

Per the erdafitinib prescribing information,2 which broadly advises withholding erdafitinib when central serous chorioretinopathy occurs, and again in collaboration with a hematologist-oncologist, the patient’s erdafitinib was withheld for 1 month, and he returned for a repeated ophthalmology examination. His VA had improved to baseline at 20/30, with improvement and near resolution of the serous fluid (Figure 4). Anterior segment examination findings were now significant for dry eyes bilaterally.

Figure 4. OCT scans of the maculae demonstrating improving retinal thickening and resolution of subretinal fluid with residual foveal changes. The right eye (bottom images) had a significant decrease in central retinal thickening, from 355 µm to 290 µm. The left eye (top images) had a significant decrease in central retinal thickening from 370 µm to 287 µm.

The patient was counseled on cautious restart of erdafitinib at a low dose, artificial tear usage, and to return for repeated imaging in 1 month. Repeated examination and imaging findings at the next office visit were stable. He elected not to resume the erdafitinib in coordination with the hematologist-oncologist due to other adverse effects (eg, myopathy) that he attributed to its use and that were hindering his quality of life. He had no other vision concerns, and he was no longer required to follow-up monthly. The patient has since died.

Discussion. Erdafitinib is a tyrosine kinase receptor inhibitor that is most specifically used for its activity against fibroblast growth factor receptors (FGFRs). The inhibition of phosphorylation of the FGFR complex blocks the signaling cascades that regulate many intracellular processes such as cell division, and in so doing, it can prevent many downstream oncogenic processes. Erdafitinib is used for its antitumor activity in FGFR-expressing cancer-cell types, which include certain types of urothelial cancer. Its current FDA-approved indications for use include locally advanced or metastatic urothelial carcinoma with susceptible fibroblast growth factor receptor 2 (FGFR2) or 3 (FGFR3) gene expression and that has progressed during or after a platinum-containing chemotherapy within the last 12 months.3,4

The median survival rate for metastatic urothelial carcinoma is typically 7 to 9 months with traditional platinum-based chemotherapy. With erdafitinib, the median duration of overall survival was 13.8 months.5

Erdafitinib has a number of notable ocular adverse effects, with most common being dry eye (28%) and central serous chorioretinopathy/retinal pigment epithelial detachment (CSCR/RPED) (25%). The median time to first onset of CSCR/RPED has been quoted at 50 days, with laterality unspecified.4,5 In our patient’s unique case, acute onset of bilateral symptomatic CSCR/RPED occurred within the first 4 weeks of starting treatment.

Erdafitinib’s mechanism of action is to inhibit FGFRs that express certain genetic sequence variations, and fibroblast growth factor is known to play an essential role in both DNA synthesis and growth of the RPE cellular layer and in preventing apoptosis of mature RPE cells.6 It can be proposed, then, that in some cases, erdafitinib mistakenly binds to normal FGFRs in the RPE and subsequently causes their dysfunction, leading to CSCR/RPED.

CSCR is a disease of the choroid in which the capillaries at this level are hyperpermeable and can lead to a detachment of the overlying retinal pigment epithelium and subretinal fluid. It is typically related to and associated with type A personalities, use of corticosteroids, autoimmune diseases, sleep disturbance/sleep apnea, and periods of high stress.7 Arguably, patients with such advanced cancer can be assumed to meet more than one of these risk factors that would predispose them to having CSCR at baseline, which may be asymptomatic.

The prognosis of typical CSCR cases is self-resolution in 2 to 3 months, usually with recovery of VA within 3 months. However, some data suggest that up to 15% of patients have persistent symptoms with persistent subretinal fluid.8 These patients, even with RPED resolution, may have residual atrophy of the RPE, which can permanently affect final best corrected VA.8

In the case of medication-induced CSCR, such as that associated with erdafitinib, withdrawing the medication is the best management approach. Many other treatment strategies exist for CSCR, from medical to surgical/procedural, that are beyond the scope of this report. The erdafitinib prescribing information states, “Perform monthly ophthalmological examinations during the first 4 months of treatment and every 3 months afterwards, and urgently at any time for visual symptoms,”2 which may not suggest the need for baseline testing but rather only monthly ophthalmologic examinations after the start of therapy. As suggested by this case report, baseline testing may be appropriate before the start of erdafitinib to ensure that there is no prior existing retinal disease that could be further compounded by the start of this medication.

Conclusions. Current recommendations may not suggest baseline testing but only monthly ophthalmologic examinations after the start of erdafitinib. As suggested by this case, bilateral serous detachments can occur acutely after start of therapy, and the extent of the involvement of the detachment guides management. We suggest that baseline testing may be beneficial before the start of this medication, as was done in our patient, to promote the best vision outcomes.

We acknowledge that in this patient population, it may not be feasible to have a full examination with OCT imaging prior to start of erdafitinib. In these situations, it is prudent to educate the patient on the adverse effects before starting the medication and on self-monitoring for signs of decreased VA with at-home VA charts or Amsler grid cards. A subjective decrease in VA could then trigger a more thorough in-office evaluation. Metamorphopsia on an Amsler grid card would similarly prompt an office evaluation. The overall survival prognosis for these patients is guarded, but when quality of life is taken into account, preserving vision cannot be undervalued.

REFERENCES:

- Adhi M, Duker JS. Optical coherence tomography—current and future applications. Curr Opin Ophthalmol. 2013;24(3):213-221. doi:10.1097/ICU.0b013e32835f8bf8

- Balversa. Prescribing information. Janssen; 2019. Accessed November 24, 2020. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/nda/2019/212018Orig1s000Lbl.pdf

- Porębska N, Latko M, Kucińska M, Zakrzewska M, Otlewski J, Opaliński Ł. Targeting cellular trafficking of fibroblast growth factor receptors as a strategy for selective cancer treatment. J Clin Med. 2018;8(1):7. doi:10.3390/jcm8010007

- Balversa. Prescribing information. Janssen; April 2020. Accessed November 17, 2020. http://www.janssenlabels.com/package-insert/product-monograph/prescribing-information/BALVERSA-pi.pdf

- Loriot Y, Necchi A, Park SH, et al; BLC2001 Study Group. Erdafitinib in locally advanced or metastatic urothelial carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2019;381(4):338-348. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1817323

- van der Noll R, Leijen S, Neuteboom GHG, Beijnen JH, Schellens JHM. Effect of inhibition of the FGFR–MAPK signaling pathway on the development of ocular toxicities. Cancer Treat Rev. 2013;39(6):664-672. doi:10.1016/j.ctrv.2013.01.003

- Liew G, Quin G, Gillies M, Fraser-Bell S. Central serous chorioretinopathy: a review of epidemiology and pathophysiology. Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2013;41(2):201-214. doi:10.1111/j.1442-9071.2012.02848.x

- Gilbert CM, Owens SL, Smith PD, Fine SL. Long-term follow-up of central serous chorioretinopathy. Br J Ophthalmol. 1984;68(11):815-820. doi:10.1136/bjo.68.11.815